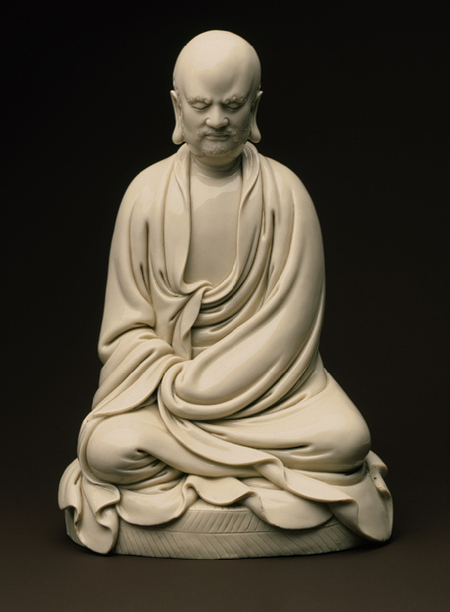

Bodhidharma

(Ming dynasty /1368–1644 / 17th century)

China

China

Profesor Francisco Duque Videla.

Es de común aceptación que el Budismo se distingue por dos corrientes de pensamiento que se oponen doctrinalmente a pesar de la común paternidad y dependencia con las enseñanzas de Gautama. Nos referimos al Mahayana (Gran Vehículo) y al Hinayana (Pequeño Vehículo).

El Ideal Mahayánico se puede simbolizar por el Bodhisattva que representa la Doctrina del Corazón o de la Compasión infinita hacia todos los seres, reconociendo que todos tienen la posibilidad de participar de la Iluminación, y, en cierto modo, la liberación del Bodhisattva se ve justificada sólo si conduce y acoge a todos los seres, renunciando al Nirvana.

De ahí que se le haya denominado «Gran Vehículo», con el objeto de transportar a todos hacia el objetivo final. Por el contrario el Hinayana privilegia la iluminación individual y suele verse en el Arhat, el símbolo del que se libera de la ilusión sin renunciar al Nirvana, y por lo tanto sin pensar en el resto de los seres como condición.

Los seguidores del Mahayana afirman que la doctrina original del Buda es genuinamente mahayánica, y que Kasyapa, su principal discípulo, habría conservado las enseñanzas esotéricas o Doctrina del Corazón encargando a Ananda la difusión de la religión o Doctrina del Ojo, pero es muy probable que Nagarjuna, en el siglo I, le haya otorgado un verdadero cuerpo doctrinal y orientación al Mahayana, cuya esencia es conservada y transmitida por Bodhidharma cinco siglos más tarde.

El Budismo en China

El Budismo entró en China probablemente unos tres siglos a.C. Algunas teorías indican que habrían sido misioneros enviados por el emperador Asoka a través de la ruta comercial de la seda como ocurrió con la expansión hacia África y Europa.

Algunos cronistas de la Dinastía Han se refieren a los cultos budistas del valle del Ganges y se relaciona al emperador Huang-Ti (246-209 a.C.) con monjes provenientes de India que habrían intentado predicar el Budismo infructuosamente.

La versión china de la entrada del Budismo es atribuida al emperador Ming-Ti (siglo I), quien habría soñado con la figura del Buda, lo que se interpretó como un signo del Cielo para la adoración de un nuevo dios. Ming-Ti envió entonces una gran embajada hacia el oeste para encontrar las señales del mensaje. Esta volvió más tarde con numerosos monjes y dos sabios budistas indos, haciéndose construir una pagoda budista. Más tarde, decenas de monjes y bikhus llegarían desde la India y otros países para predicar la nueva fe en China.

Sin embargo el Budismo tropezó con algunas dificultades al asentarse en este nuevo territorio por sus propias características, que chocaron de un modo inconveniente con el pensamiento social imperante y no se adaptaron fácilmente a las doctrinas de Confucio. En primer lugar el desarraigo familiar y político del Budismo no era compatible con el sentimiento más acendrado del pensamiento confuciano: la piedad filial, el culto a los antepasados y el ajuste a las normas y procedimientos sociales estrictos entre los que se contaba la autosuficiencia y la responsabilidad político-social. Si el Budismo logró simpatizantes es porque se asemejaba bastante más -al menos en lo doctrinal- al Taoísmo, mucho más liberal y alejado del mundo.

No cejaron los esfuerzos por incrementar la participación budista en China, y en el 335, bajo la Dinastía Tsin del este, el sabio Budhojhanga, traductor de grandes obras al chino, entre ellas el Dhammapadha, logra el reconocimiento oficial del Budismo. En el 405 se produce la llegada de Kumarajiva, que aporta una gran cantidad de obras y da origen a algunas corrientes que hacían hincapié en el conocimiento intelectual de la doctrina. Posteriormente encontramos a Paramartha que llega en el 546 y también se dedica a la difusión de las obras y exposiciones del Mahayana.

Quizás este exceso de erudición mantuvo al Budismo confinado a la corte y se limitó a discusiones entre algunos expertos, pero no consigue impactar en la mentalidad y la búsqueda de la sabiduría de los chinos.

Por ello se hacía necesaria una asimilación de la idiosincrasia china al Budismo y se piensa que el éxito de esta fórmula radica principalmente en el pensamiento de Bodhidharma y la doctrina del Zen.

Aparición de Bodhidharma. Fuentes Históricas

Como sabemos, en el largo desarrollo de la Humanidad se han confeccionado dos Historias que corren paralelamente como afluentes de un mismo río, por lo que intentaremos esbozar lo poco que se conoce en ambos sentidos sobre la presencia de Bodhidharma como personaje histórico.

La figura de Bodhidharma (Ta-Mo en China y Budai-Daruma-Daishi en Japón) resulta muy controvertida históricamente hablando. Algunos eruditos aún hoy ponen en duda su existencia debido a la escasa información con que se cuenta.

Las fuentes que se reconocen como más o menos auténticas serían:

-Biografías de Monjes Ejemplares, de Tao-hsuan escrita hacia el 645.

-Los Anales de la Transmisión de la Lámpara, de Tao-yuan escrita hacia el 1002.

Según estos textos, Bodhidharma nació alrededor del año 440 en la ciudad de Kanchi, capital del reino Pallava (sur de la India). Era el tercer hijo del rey Simhavarman y brahmín por nacimiento. Convertido desde joven al Budismo, recibió instrucción de Prajnatara, que había sido llamado desde Maghada por su padre, y es él mismo quien le incita a ir hacia China.

Cerrada la ruta comercial por las invasiones de los Hunos, Bodhidharma se embarca en el cercano puerto de Mahabalipuram, recorriendo el sur de la India y la península maláyica; tarda unos tres años en llegar al puerto de Nanhai, en el sur de China, por el año 475.

Como China se hallaba dividida en las Dinastías Wei en el norte y Liu Sung en el sur, la mentalidad imperante producía algunas diferencias en la asimilación del Budismo por parte de los norteños y sureños, siendo estos últimos de corte más intelectual y erudito y poco dados a la práctica. Habría permanecido visitando monasterios budistas, que según censos de la época llegaban a unos 2000 con un clero de 36.000 personas en el sur y 6500 templos con 80.000 integrantes en el norte. Tao-yuan fecha la llegada de Bodhidharma en el 520 (unos 45 años más tarde que la versión de Tao-hsuan) donde sería acogido por el emperador Wu de la Dinastía Liang, siendo invitado a la capital Chienkan para una entrevista que resultó poco productiva, pues frente a la profunda piedad y esfuerzo en los méritos que le expuso el Emperador, Bodhidharma predicó el origen de su misión expresado en los siguientes términos: «Una transmisión especial fuera de las escrituras, con ninguna dependencia de las palabras o de las letras, dirigiéndose directamente hacia el alma del hombre, contemplar su propia naturaleza y realizar el estado de Buda».

La tradición quiere que haya anunciado su misión con estas palabras:

La razón original de mi venida a este país fue transmitir la Ley, a fin de salvar a los confusos. Una flor de cinco pétalos se abre, y la producción del fruto vendrá de por sí.

Este contraste con el Emperador lo lleva a cruzar el Yangtzé e instalarse en el norte. Permanece cerca de Pingcheng y probablemente sigue a los monjes que se trasladaron con el emperador Hsiao-wen a su nueva capital Loyang a orillas del río Lo, en el 494 -según Tao-hsuan-. En el 496, el Emperador ordena la construcción del templo de Shaolin, en el monte Sung, provincia de Honan, al sudeste de Loyang, para otro maestro indo, pero es Bodhidharma el que se instala en sus dependencias y le otorga la fama posterior.

Se dice que en el pico Shaoshi del monte Sung, Bodhidharma se refugia en una caverna para permanecer sentado meditando frente a una pared rocosa, situada a un kilómetro del templo, por ello es conocido como Pikwan Po-lo-men, o «el Brahmán que mira la muralla».

En su estancia en Loyang, probablemente en el templo Yungming, que albergaba a monjes extranjeros (que hacia el 534 acogía a unos 3000 provenientes hasta de Siria), ordenó a un monje llamado Sheng-fu, que poco después partió hacia el sur sin haber predicado la doctrina. Luego se menciona a Tao-yu, que permaneció con Bodhidharma unos 5 ó 6 años y que aun cuando entendió el Camino nunca enseñó; y Hui-k’o, que se convertiría en su sucesor y depositario del manto y el cuenco sagrado, reliquia que Bodhidharma habría traído desde la India y que sería el empleado por el propio Buda para la limosna; además se dice que le entregó una traducción del Sutra Lankavatara.

La leyenda quiere que Hui-k’o haya sido manco habiéndole presentado el brazo cortado como testimonio de su inconmovible voluntad de transformarse en su discípulo.

Luego, en el 528 y poco después de haber transmitido su doctrina a Hui-k’o, muere envenenado por un monje celoso. Según Tao-yuan, los restos de Bodhidharma fueron enterrados en el templo de Tinglin, en la montaña de la Oreja del Oso, cerca de Loyang. Después de esto, que puede ser más o menos verídico, la leyenda afirma que tres años más tarde, un funcionario que caminaba por las montañas de Asia central se encuentra con Bodhidharma, quien le explica que se marcha hacia la India; llevaba un bastón con una única sandalia colgando. Este encuentro despierta la curiosidad de los monjes que acuden a la tumba del Maestro, verificando que se encontraba vacía con una única sandalia en su interior.

H. P. Blavatsky afirma en su Doctrina Secreta que la misión de Bodhidharma es refundar el Budismo Esotérico de la Escuela Tsung-Men, la verdadera Doctrina del Corazón, subdividida más tarde en cinco escuelas, lo que se infiere de sus palabras acerca de la flor de cinco pétalos.

Se discute todavía si dejó escritos o si su enseñanza era meramente intuitiva y carente de explicaciones. Blavatsky le otorga autoría sobre diversos libros y los estudiosos le atribuyen tradicionalmente, aunque discutible, las siguientes obras: Meditación sobre los Cuatro Actos, Tratado sobre el Linaje de la Fe, Sermón del Despertar, Sermón de la Contemplación de la Mente.

Además suele otorgársele autoría sobre un pergamino denominado el I-Chin-Ching, tratado que contendría instrucciones formativas de carácter psicofísico que se interpretarían como la base -y única relación- con ejercicios de artes marciales, ya que estaban destinados a fortalecerlos física y psíquicamente con el objeto de facilitarles la ascesis hacia los estados de conciencia superiores; sin embargo estas últimas referencias no se encuentran contenidas en las biografías tradicionales.

Estos textos se encuentran clasificados dentro de la exposición exotérica y forman parte del Ch’ang o escuela Zen que se estructuraría después de él, principalmente a partir del Sexto Patriarca Hui-Neng.

Ahora, acerca de la difundida paternidad de Bodhidharma sobre las artes marciales de Shaolin, en sentido estricto, no existen referencias en ninguna de las dos fuentes mencionadas, y para afirmar -aparte del texto antes mencionado- el desarrollo de ejercicios o sistemas gimnásticos psicofísicos marciales a la manera del Hatha-yoga, debemos dejar espacio a la leyenda que corre paralela a la historia. En este último tema, se suele atribuir a Bodhidharma la preparación de los monjes, con el objeto no sólo de fortalecer sus condiciones sino además capacitarse para la defensa, motivada por el relativo aislamiento del Templo y la peligrosidad de los caminos infestados de bandidos y animales feroces.

Algunos relatos dicen que el Maestro transformó brazos y piernas en eficaces armas de combate, otorgándole un prestigio sin igual al naciente estilo del Shaolin-Shu, enriquecido muy probablemente con elementos parapsicológicos, cosa que era común entre los monjes budistas como acaeció con los primeros que arribaron en la época de Huang-Ti y que escaparon de un modo milagroso tras haber sido víctimas de torturas y encierros.

Posteriormente esta fama creció de un modo extraordinario y muchos militares que huían de los manchúes se refugiaron en el Templo aportando su propia experiencia al estilo e incrementando la complejidad de su prácticas de modo tal que siglos más tarde sería imposible distinguir la huella de Bodhidharma entre el entramado de técnicas con armas y sin armas que constituían la base de varias formas de lucha atribuidas a Shaolin.

Referencias Míticas

Como en todos los casos de la historia de los Adeptos, su vida se encuentra plagada de mitos y leyendas que ensalzan y justifican el increíble impacto, que tan nebulosa existencia dejó en el misticismo budista chino, sólo comparable al de la vida y enseñanzas del propio Gautama.

Por ejemplo se relata que cuando Bodhidharma sostuvo el encuentro con el emperador Wu, éste le expuso la imperiosa necesidad de practicar actos piadosos y del mérito de las obras como condición para alcanzar el estado de Buda. El Maestro le replicó que ni el mérito ni las buenas obras acercaban al discípulo ni un ápice hacia la Iluminación, que antes bien, la ruptura de todo condicionamiento mental, de todo prejuicio, eran necesarios para alcanzar el Budhado. Como el Emperador se mostrara contrariado por esta respuesta, Bodhidharma abandonó la corte sin mediar otra insinuación. Más tarde, y aconsejado por sus asesores, envió en la búsqueda del Maestro, pero el emisario lo perdió de vista cuando cruzaba el Yangtzé sobre un junco hueco.

Ya instalado en la caverna frente a la pared rocosa cerca de Shaolin, quiere la tradición que, al buscar Bodhidharma el estado de Iluminación necesario para la fundamentación de la existencia, se haya distraído con la imagen de una hermosa mujer (la tentación de Mara) y para resolver esto, decide meditar sobre un objeto o símbolo hasta detener el flujo mental. Como lo venciera el cansancio a menudo, decidió arrancarse los párpados y arrojarlos fuera de la cueva en la que habitaba.

Pasado largo tiempo (nueve años según la leyenda) y habiendo logrado su propósito, bebió una pacificante bebida obtenida de unas hojas que crecieran del lugar en donde cayeron sus párpados, y esta planta fue luego conocida como Té. De un modo inequívoco se lo pinta o representa en esculturas con ojos saltones y carentes de párpados.

Su proveniencia mítica se identifica con el Cielo occidental o Shamballah, Patria legendaria de la jerarquía de Adeptos y salvadores.

Hasta él se acercó el que sería su discípulo Hui-k’o, quien, proviniendo de un linaje guerrero, habría llegado a despojarse de un brazo con su sable para demostrar así su fidelidad y su deseo de ser instruido. Aceptado ya, debió aún lanzarse al vacío y ante una muerte segura salió ileso, en virtud a la firme convicción de seguir a su Maestro.

En su sucesión y hasta el Sexto Patriarca cabe hacer notar un hecho que si bien tiene un carácter simbólico sería digno de un artículo aparte. El traspaso de la doctrina se realizó en línea directa hasta el Quinto Patriarca, el cual tuvo dos discípulos al momento de su sucesión. Por un lado Hui-Neng es reconocido como el Sexto Patriarca del Budismo Zen y el verdadero iniciador de esta Escuela y se caracteriza por sus respuestas y conducta paradójicas propias de todos los maestros del Zen.

Su origen es humilde y se resalta su carácter iletrado frente al del otro discípulo Shen-Hsiu, quien tomado por un erudito, representa vulgarmente al intelectual dogmático. Se dice que el manto de Bodhidharma habría sido entregado junto a la Doctrina hasta el Quinto Patriarca, pero éste se lo legó a su discípulo Hui-Neng por su mayor intuición del Zen, después de un concurso de poemas en que Shen-Hsiu, haciendo gala de sus conocimientos, ilustró a la mente como un espejo que debía ser limpiado. Hui-Neng respondió al desafío con un poema típicamente Zen; «No habiendo mente ni espejo, no hay nada que limpiar».

El Maestro le otorgó la victoria, sin embargo le instruyó en relación a no entregar el manto posteriormente a nadie, ya que esto no era necesario en lo sucesivo. Siendo Shen-Hsiu el naturalmente designado para tal honor y habiendo vencido a Hui-Neng en la disputa doctrinal, se generó una discordia entre los discípulos de ambos. Más tarde Hui-Neng se va hacia el sur y funda su Escuela, que daría origen y desarrollo al Zen propiamente tal con sus características tan difundidas en nuestros días.

El origen de esta transmisión de la Enseñanza Interna se remonta al mismo Gautama y su discípulo Kasyapa quien -quiere la tradición- habría despertado a la Iluminación tras el enigmático sermón dado por el Buda en la Montaña Pico de Buitre, cuando levantó entre sus dedos una flor que sus discípulos le habían entregado, recogida de entre las diversas ofrendas depositadas por los numerosos concurrentes, esbozando una sonrisa. Tras un prolongado silencio, Kasyapa sonrió a la vez; enseguida el Buda se retiró dando por terminado el sermón. Los budistas zen quieren ver los orígenes de la Escuela del Zen en este encuentro, y el inicio de la Doctrina Secreta del Budismo.

Enseñanza de Bodhidharma

Las biografías antes mencionadas sólo dicen que Bodhidharma enseñó «Contemplación de la pared» y las cuatro prácticas descritas en la Meditación de los Cuatro Actos.

Estas escuetas referencias pueden extenderse y fundamentarse otra vez en lo que afirma H.P. Blavatsky cuando habla de la Doctrina del Ojo y la Doctrina del Corazón. La denominada Doctrina del Ojo, es la contenida en las escrituras exotéricas y difundidas en un cuerpo religioso principalmente hacia el sur de la India y cobijada en el Hinayana. La enseñanza esotérica o Doctrina del Corazón sería la base del Mahayana, extendida hacia el norte y refugiada en el Tíbet y China, primero a través de Nagarjuna y Aryasangha y continuada de un modo estrictamente ordenado de Patriarca a Patriarca por lo menos hasta la época de Bodhidharma. Este, dice Blavatsky, es, junto con Nagarjuna, un reformador y autor de las obras más importantes de la escuela china de contemplación (Dan o Ch’ang de Dhyana).

Agreguemos además algunas referencias de la historia de Hui-k’o, sucesor de Bodhidharma. En el 534 el emperador Hsiao-wu muere asesinado y el reino norteño de Wu se dividió en dos dinastías Wei. A consecuencia de continuos ataques a la ciudad de Loyang, Hui-k’o se refugió probablemente en Wei oriental debido a que los gobernantes eran budistas y acogieron a todos los monjes que huían del conflicto. En la capital, Yeh, conoce a T’an Lin, erudito budista que traducía y prologaba sutras. Este encuentro despierta el interés de T’an Lin por las enseñanzas y escribe un prefacio a la Meditación de los Cuatro Actos. Hasta ahí la historia recoge datos sobre Bodhidharma.

Aunque el Maestro había sido antecedido por otros eminentes budistas de las escuelas contemplativas, la aparición fugaz y oscura de Bodhidharma provocó un increíble impacto. Si entendemos que sólo un discípulo es el depositario de tan extraordinaria revolución espiritual, no podemos explicarnos su difusión y enorme prestigio. No sabemos nada más, por razones obvias, acerca del trabajo de Bodhidharma y sus cinco ramas esotéricas, probablemente el verdadero fundamento de tal impacto, pero al parecer nos han quedado claros ejemplos de su enseñanza más popular, y siempre dentro de la línea contemplativa, el Zen.

Existen buenas razones para creer que los antecedentes contemplativos de Bodhidharma transmitieron los principios fundamentales del Sunyata, o «contemplación de la vacuidad del mundo», que enseña el Mahayana y que deriva en el Wu-wei-che-jen o estado de «verdadero hombre sin posición», el estado de Budha; pero se los suele simbolizar en el cojín de la meditación o las prácticas relacionadas con el Tantrismo que dieron origen a escuelas chinas y japonesas de Budismo. Sin embargo Bodhidharma lleva su enseñanza de la mano de la espada que Prajnatara -según cuenta la leyenda- le entregó junto con la doctrina, para cortar firmemente las ligaduras con el mundo y no remitirse a una purificación de la mente en una simple internalización que se asemeja más al Hinayana.

No abandona los sutras, y de hecho vuelve a ellos sin cesar, pero su transmisión es eminentemente práctica y está claramente orientada a la salvación del mundo, o sea es en esencia Doctrina del Corazón. En los cuatro sermones ya mencionados, y de los cuales se tienen versiones ahora muy antiguas, pues a principios de siglo se hallaron miles de manuscritos budistas de los siglos VII y VIII, época T’ang, en las Grutas de Tuhuang en China, que han sido trabajados y traducidos, se encuentran contenidas las enseñanzas recopiladas de Bodhidharma; las menciones a sutras son principalmente del Nirvana, Avatamsaka y Vimalakirti.

La Meditación sobre los Cuatro Actos

Este sermón describe brevemente la entrada al Camino a través de la razón (contemplación) y la práctica. La razón dice: «…significa comprender la esencia mediante la instrucción (la necesidad de un Maestro) y creer que todos los seres vivos comparten la misma naturaleza…», abandonando la ilusión, entrando en comunión con la cadena humana. Las cuatro prácticas son: sufrir la injusticia, o aceptación del Karma; adaptarse a los condicionamientos de la existencia; no buscar nada o matar el deseo; y practicar el Dharma. Las Cuatro Nobles Verdades.

El Tratado sobre el Linaje de la Fe

Propone que la búsqueda del Buda más allá de la Mente, como Yo real, es absurdo, y sostiene la perfecta identidad del Ser Interno o Propia Naturaleza con el Buda. Además hace hincapié en la inutilidad de las buenas obras y el mérito o el apego a la doctrina y la recitación de los sutras, frente al desvelamiento de la propia Naturaleza, como única vía de Iluminación.

El Sermón del Despertar

Este texto habla sobre la naturaleza del Nirvana o del estado de Iluminación que adviene tras el desapego total de las apariencias de este mundo, que generan en nosotros la sensación de lo agradable y lo desagradable, mediante lo cual se condiciona el Karma. Menciona aquí el vocablo Zen y lo define como un estado de vida en que se permanece inalterable, descondicionado y despierto, pero a la vez entregado a la caridad sin ningún tipo de pesar y renunciando a los frutos de dicho estado. El origen del sufrimiento es el mismo que el del Nirvana, por lo tanto se agota el sufrimiento en su vacío. Existe un necesario encadenamiento entre los Budas y los mortales cuando dice: «Los mortales liberan a los Budas y los Budas liberan a los mortales».

El Sermón de la Contemplación de la Mente

En la mente se encuentra la raíz de todas las cosas. El Sutra del Nirvana dice: «Todos los mortales cuentan con naturaleza búdica. Pero se halla cubierta con la oscuridad de la que no pueden escapar. Nuestra naturaleza Búdica es conocimiento: conocer y hacer que otros conozcan a otros. Realizar el conocimiento es la liberación». O sea, la contemplación de la mente es conocimiento. Conocimiento es ayudar a otros al propio conocimiento. La realización total del conocimiento es la liberación de todos los mortales.

Tres venenos infunden la muerte y la perdición: el odio, la codicia y la ilusión. El Camino Moral, la Meditación y la Iluminación son las vías para contrarrestarlos. Esto se ve mejor explicado en las seis Paramitas o Caridad, Moralidad, Paciencia, Devoción, Meditación y Sabiduría. Explica que las referencias a las obras meritorias como la construcción de monasterios, la recitación de los sutras, la prescripción de alimentos o las purificaciones, son el símbolo de prácticas internas que tienen que ver con la localización de determinados motores ocultos en la naturaleza humana, por lo tanto valorizar el contenido de las obras sin las prácticas discipulares es caer en la ilusión y atenerse a las consecuencias kármicas de lo bueno y lo malo.

Como vemos, estos sermones se encuentran plenamente imbuidos de la doctrina Mahayánica de la compasión hacia todos los seres y el necesario encadenamiento de sabios y mortales para liberar a toda la Humanidad.

Es la genuina enseñanza de los Maestros de Sabiduría que floreció de modo extraordinario en la oculta Transmisión de la Ley de un monje que vino del oeste para traer el Zen y algo más.

--------------------------------------------------

The Great Bodhidharma

Question

According to Bodhidharma,

Many roads lead to the Path, but basically there are only two: reason and practice.

To enter by reason means to realize the essence through instruction and to believe that all living things share the same true nature, which isn't apparent because it's shrouded by sensation and delusion.

To enter by practice refers to four all-inclusive practices: suffering injustice, adapting to conditions, seeking nothing, and practicing the Dharma.

(from Bodhidharma's teachings)

1. To which road that the legacy of Bodhidharma (18 Lohan Hands, Yi Jin Jing, Bone Marrow Cleansing, and Zen) will lead us to, to enter the Path by reason, by practice, or both?

2. Why did the Great Bodhidharma put the emphasize on the Path, and not the destination?

-- Sifu Joko Riyanto

Answer

We need to appreciate the limitation of words. Firstly, words may not convey the exact meaning the speaker or writer intends them to be. Secondly their interpretation is much influenced by the experience and understanding of those who hear or read the words.

In this case, we have a third factor of time and a fourth factor of translation. Bodhidharma's teaching was given more than 1500 years ago, and translated from Sanskrit to classical Chinese to modern Chinese and then to English.

Considering these four factors we can better appreciate that what many people understand by reading Bodhidharm's teaching today may not be what Bodhidharma himself meant.

To help modern readers, I shall change some words which I believe better express what Bodhidharma meant, as follows:

Many methods lead to Enlightenment, but basically there are only two: wisdom and cultivation.

To enter by wisdom means to realize the Supreme Reality through philosophy and to know that all living things share the same true nature, which isn't apparent because it's shrouded by sensation and delusion.

To enter by cultivation refers to four all-inclusive practices: tolerance, perseverance, renouncing world affairs, and practicing the Dharma.

Bodhidharma taught that there are many ways to attain Enlightenment, but all these ways can be classified into two main categories, namely wisdom and cultivation.

To attain Enlightenment through wisdom, an aspirant realizes that everything in the phenomenal world shares the same True Nature, called differently by different people such as Tathagata, God the Holy Spirit, and the Great Void.

This True Nature is not apparent to people because it is shrouded by people's sensation and delusion due to their interpretation of the True Nature through their gross sense organs.

In modern scientific terms, it means that everything in our phenomenal world is undifferentiated energy, but after going through their eyes, ears, nose, mouth, skin and mind, people interpret this undifferentiated energy as differentiated entities like individual persons, cats, elephants, mountains and countless other living and non-living things.

To attain Enlightenment through cultivation, an aspirant has to be tolerant (including tolerant of other people's beliefs which may be different from his), persevere against all odds, renounce all world pleasures like eating meat and enjoying sex, and practice the teaching as taught by established masters.

The road via wisdom is the road of Zen. It is pointing directly at the mind and attaining Buddha Nature in an instant.

The road via cultivation is the road of other Buddhist schools, especially Theravada Buddhism. It is poetically described as "teaching within the tradition".

It is pertinent to note that the above teaching was given by Bodhidharma to Shaolin monks, who had voluntarily renounced worldly lives. If you are a lay practitioner, it is fine if you eat meat and enjoy sex. But if one is a Shaolin monk, or claims to be, eating meat and having sex, regardless of whether he enjoys it, are not only against Bodhidharma's teaching but are two of the five cardinal sins in Mahayana monkhood.

With this background understanding, we can now better answer your two questions.

1. To which road that the legacy of Bodhidharma (18 Lohan Hands, Yi Jin Jing, Bone Marrow Cleansing, and Zen) will lead us to, to enter the Path by reason, by practice, or both?

As is often the case in our school, the answer can be by reason, by practice, by either one road, by both or by none, depending on various factors.

Although the Shaolin arts were taught by Bodhidharma to enable Shaolin monks to attain Enlightenment, this is not our aim in Shaolin Wahnam. We are still worldly. We still wholesomely enjoy eating meat, having sex and other worldly pleasures. So to us the answer is neither road. Practicing the legacy of Bodhidharma does not lead us to the road of reason or practice to enter the Path -- at least not now when we are not monks.

Nevertheless, though we are not ready yet to enter the path of monkhood, practicing the legacy of Bodhidharma will give us not only a glimpse but the actual benefits that Shaolin monks in the past received from Bodhidharma. These numerous benefits may be summed up into two categories, namely giving us meaning in life, and enabling us to live lives more rewardingly. Hence, the legacy leads us to both the road of reason and the road of practice.

In practical situations, Bodhidharma's legacy may lead some of our students to the road of reason, and some to the road of practice. While practicing any of the arts, some of our students may expand into the Cosmos, and realize experiencially that everything is of the same True Nature. Other students may not have such a spiritual experience, but become more tolerant and determined in whatever they do.

Now we come to your second question.

2. Why did the Great Bodhidharma put the emphasize on the Path, and not the destination?

It is a matter of interpretation. You may interpret that the "Path" as the journey, some may interpret it as the destination, yet others may interpret it as both the journey and the destination.

This is a hallmark of great teaching. It fulfils the aspirations of practitioners according to their needs and developmental stages.

Basically, Bodhidharma's teaching is as follows. You can attain Enlightenment by realizing cosmic wisdom or following established practice. The destination is the same, though people may call it by different names. There are many ways to reach the destination, but the many ways may be classified as by wisdom or by practice.

-- Grandmaster Wong Kiew Kit

-----------------------------------------

DARUMA - Father of Zen Buddhism

From Buddhahood to Brothel, From Saint to Sinner

The Evolution of Daruma Artwork in Japan

Sanskrit = Bodhidharma; a sage from India

Chn. = Pútídámó 菩提達磨, Dámó, Damo, Tamo

Jp = Daruma 達磨, Bodaidaruma 菩提達磨

Jp. = Daruma Daishi 達磨大師, Krn. = Dalma, Talma 달마

Tibetan = Bodhidharmottāra or Dharmottāra; considered an Arhat.

In Tibet/China/Japan, he is an avatar of Avalokitêśvara (J = Kannon).

In Japan, famous monks like Gyōki & Eisai are his avatars.

In Tamil Nadu (southern India), he is known as போதிதர்மன்

Bodhi = Enlightened, Dharma = Universal Law. Details Here.

Bodhidharma (Daruma) 達磨図

By Hakuin Ekaku 白隠慧鶴 (1685-1768). H 122.0 cm x W 58.2.

Tokeii Temple

DARUMA MENU

Intro

Portrait Paintings

Scenes from His Life

Smallpox Talisman

Phallic Talisman

Female Daruma

Consorting with Women

Single Brush Daruma

Tumbler Dolls

Other Associations

A-to-Z Glossary of Forms

BACKGROUND NOTES

Early Chinese Texts

Encounter with Emperor Wu

Zen Intro to Japan

Tea, Zen, & Daruma

Martial Arts & Daruma

References

Daruma Doll. Details Here.

Armless, legless, & blind (no pupils).

One of modern Japan's most poplular talismans of good luck.

Paint in the left eye when you make your wish. Paint in the righte ye when your wish is granted.

Daruma as taliman to ward off

smallpox. Details Here.

Photo Prints of Japan

Wall-Gazing Daruma 面壁達磨

Phallic Symbol. Details Here.

By Shaku Sōen 釈宗演 1860-1919.

Photo Tokeiji Temple

Onna Daruma 女達磨.

Female Daruma. Details Here.

Daruma and Courtesan

by Katsukawa Shunkō 勝川春好(1743~1812). Details Here.

Practically nothing is known about Bodhidharma or his teachings. Early Chinese texts provide scant information, except to say he was a pious monk from Indian who came to China and introduced a form of meditation that involved "gazing at cave walls." Only one of the ten textsattributed to Bodhidharma is presently considered authentic. <Broughton, p. 4

CHINESE LEGENDS. The best-known Chinese legends say he was the third son of a Brahman king from southern India [possibly from Tamil Nadu) and studied under the tutelage of Prajñātāra 般若多羅 (Jp.. = Hannyatara), the 27th Indian Patriarch in a direct mind-to-mind line of transmission from the Historical Buddha. Bodhidharma achieved enlightenment (Japanese = satori さとり), becoming the 28th Indian Patriarch in that lineage (Nijūhasso 二十八祖), and then, in accordance with instructions from Prajñātāra, he traveled to China to transmit theMahayana teachings. After a perilous three-year sea voyage, he finally reaches Canton (China), whereupon he makes his way to the court of the Liang Dynasty in Nanking (Nanjing) and speaks with Emperor Wu (Liáng Wǔdì 梁武帝; Jp. = Ryō Butei). The pious monarch, one of China's most fervent patrons of Buddhism, is told that his building of temples, ordaining of monks, carving of Buddha statues, and copying of sutrus has no karmic merit (see story here). The emperor is puzzled and perhaps annoyed, so Bodhidharma makes a quick getaway, heading northward to Shaolin Temple (Jp. = Shōrinji 少林寺) on Mt Song (Jp. = Sūzan 嵩山) in the state of Wei. To reach his destination, he must cross the mighty Yangtze River (artwork of this scene shows him crossing the river while balanced atop a tiny reed). At Shaolin Temple, he meditates for nine years in a cave, gaining the name Wall-Gazing Brahman 壁觀婆羅門 (Chn. = Bìguān Póluómén; Jp. = Hekikan Baramon or Menpeki Daruma 面壁達磨; literally the "wall-facing" or "wall-gazing" Bodhidharma.)

Bodhidharma's new meditation technique attracts few students, but one of them, Huìkě 慧可 (Jp. = Eka), is so eager to become Bodhidharma's student that he stands outside the cave in the snow and waits one whole week for the master's attention and then Huìkě cuts off his own left arm and presents it to the master to demonstrate his determination to attain enlightenment (this scene is also represented in artwork). Huìkě eventually becomes Bodhidharma's successor. Despite two unsuccessful attempts by rivals to poison Bodhidharma, the sage knowingly takes poison on their third attempt, and dies at the age of 150. Three years later, in the Pamir mountains, a Chinese diplomat named Sòng Yún 宋雲 is returning to China from a trip to the West when he meets Bodhidharma, who is on his way back to India, walking barefoot and carrying one shoe in his hand. When the diplomat finally gets home, and tells this story, the master's grave is opened and all that is found is one shoe. Bodhidharma is thereafter considered a type of Taoist Immortal, one who feigned his own death. <Faure

JAPANESE LEGENDS. Japanese stories about Daruma (Bodhidharma's name in Japan) go far beyond Chinese legends -- they are overlaid with a wealth of new mythology and superstition involving popular culture and local Japanese folkloric motifs related to astral deities, gods of the crossroads, epidemic spirits, fertility, and more. According to the Japanese, Daruma's arms and legs supposedly atrophied, shriveled up, and fell off during his nine-year meditation marathon facing a cave wall in China. During that time, Japanese legend also credits Bodhidharma with plucking out (or cutting off) his eyelids. Apparently he once fell asleep during meditation, and in anger, he cast them off. The eyelids fell to the ground and sprouted into China's first green tea plants. As we know, Zen's assimilation into Japanese culture was accompanied by the introduction of green tea, which was used to ward off drowsiness during lengthy zazen sessions. Additionally, Japan's medieval Tendai sect claims that Bodhidharma did not return to India but journeyed onward to Japan, where he met Prince Shōtoku Taishi (574 - 622 AD), the first great patron of Buddhism in Japan, and from this association, Daruma is also linked (in Japanese myth) to horses and monkeys. Details here.

The origin of these Japanese legends is hard to pinpoint. Zen came to prominence in Japan during the Kamakura period (1185-1333), although Zen teachings had entered Japan centuries earlier via China. In traditional Japanese Zen artwork (from the medieval period), Daruma is typically portrayed as a pious, stern-faced, red-robed monk pointing the way to enlightenment. But in later centuries, Daruma came to serve a wide variety of different roles. Beginning sometime in the 16th century, red-colored Daruma images became popular talismans to protect children against smallpox (the smallpox god was said to like the color red, and could therefore be pacified by red offerings). By the 18th century, red-colored Daruma dolls (with no arms or legs) were also sold to ward off smallpox. Smallpox disappeared after vaccination was introduced to Japan in the Meiji period (1868-1912), but the bright redDaruma dolls remained extremely popular as good-luck charms -- today they are one of Japan's most ubiquitous icons of good fortune. Painting in the eyes of Daruma dolls is a widespread modern practice to ensure success in business, marriage, politics, and other endeavors.

Daruma dolls are also called "tumbler dolls" (okiagari koboshi 起き上がり小法師), for when knocked on their side, they pop back to the upright position and therefore symbolize (1) a speedy recovery from illness, akin to "getting back on one's feet" and (2) resilience, undaunted spirit, and determination. Since Daruma dollsappeared without any bodily appendages, they lent themselves easily to phallic symbolism (that which falls and soon rises again is the penis), and Daruma therefore became a subject of parody by Edo-era artists who often portrayed him alongside courtesans. Says scholar Bernard Faure

One final point. In Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e 浮世絵) and paintings from the 17th century onward, Daruma is depicted more and more as weak, vain, and desirous, unable to escape the same foibles and illusions faced daily by the common folk. This latter "down-to-earth" Daruma is the deity who is today beloved by the Japanese -- not the scruffy old man in portrait paintings who stares at a wall !! Since the Edo period, Daruma has served as a source of parody, laughter, and ribaldry, more willing to dress in the clothes of a woman or manifest himself as a female than to remain forever chained inside his cave as a lofty symbol of immovable equanimity divorced from ordinary life. Poor Daruma. Japan's own scholars don't know how to categorize him in their deity dictionaries. In both old and new lexiconic works, Daruma fails to appear as aBuddha or a Bodhisattva. Rather, he appears in the closing chapters as one of Japan's so-called "Eminent Monks" -- or he doesn't appear at all. Despite this quibble, Daruma in modern Japan is a living icon, not a dead one. Daruma has forgone the rarified and perfumed abode of the gods and instead gotten "down and dirty." He lives among sinners, prostitutes, the uneducated, gamblers, farmers, the poor, the salaryman, and all who suffer daily. Daruma's aim is not to retire from the world into solitary meditation, but to stay in close touch with the ordinary labors of the people, to live not away from the community but within the community, forever carrying out the Bodhisattva's task of bringing compassion and wisdom to all. This seems (to me) to be in the true spirit of Zen, for in the end, the great truth of Zen is possessed by everyone, and the only way to gain salvation, as D.T. Suzuki once said, is to "throw oneself down into a bottomless abyss, and this, indeed, is no easy task."

Daruma Portraits in Japanese Artwork

Daruma was a favorite subject of Japanese painters, and a wide variety of brush and ink paintings are still extant. The most common portraits emphasize Daruma's "Indian (foreign)" appearance, and thus he is often portrayed as a scraggly man with bushy eyebrows and beard, a big nose, elongated ears (a symbol of enlightened beings), large circular earrings, and staring eyes without eyelids. The oldest extant portrait painting of Daruma in Japan (to my knowledge) is a hanging scroll of a seated Daruma dressed in a red robe at Kōgaku-ji Temple 向嶽寺 (Kōshū City, Yamanashi) dated to the Kamakura era (circa 1260 AD).See photo below. Portrait paintings of prominent monks and people are considered innovations of the Kamakura period, with the Zen sect in particular pursuing this form of expression. This explains why portraitures and paintings of Daruma in Japan far outnumber sculptural representations of the Zen patriarch. Portrait paintings of Japan's Zen masters served multiple functions, e.g., as a form of homage to the founders of Zen Buddhism, as an aid to help practitioners reach enlightenment, as a certificate given by a Zen teacher to a student to acknowledge the student's attainment of spiritual awareness, as a symbol confirming the unbroken lineage of a sect, or as an image used in memorial services at Zen temples. Keyword = Zenshū Soshizō 禅宗祖師像 (lit. Portraits of Zen Patriarchs).

Bodhidharma (Daruma), 15th C.

by Shōkei (Keishōki) 祥啓 (d. 1518?)

Nanzenji Temple 南禅寺, Kyoto

Bodhidharma (Daruma)

by Soga Jasoku 曽我蛇足 (d. 1483)

Yōtokuin Temple 養徳院, Kyoto

Photo Baxleystamps.com

Bodhidharma (Daruma) 15th C.

by Shōkei 祥啓 (d. 1518?)

Nanzenji

Bodhidharma (Daruma)

Unsigned, Hanging Scroll

H 76.5 cm, W 39.0.cm, Late 16 C.

Photo courtesy British Museum

Bodhidharma (Daruma)

by Takeda Mokurai 竹田黙雷 (1854-1930)

Kennin-ji Temple 建仁寺 (Kyoto).

See full image here. Photo Schumacher.

Bodhidharma (Daruma)

by Kanō Chikanobu 狩野周信

(1660-1728). Ink & Colors on Silk

Pacific Asia Museum

Daruma-zu 達磨図, Edo Period

by Shiba Kōkan 司馬江漢 (1747-1818)

At Renzōji Temple 蓮蔵寺 (Mie Pref.)

Photo from this J-site.

Daruma ga Koronda, Edo era

ダルマサンガコロンダ, 洗昇画

Waseda University Library Catalog

Photo: Wasea University Library

Daruma-zō 達磨像, Edo Era, by

Hakuin 白隠慧鶴 (1685-1768)

Manjuji Temple 萬壽寺, Oita Pref.

Photo: Kyushu Nat'l Museum

Red-Robed Bodhidharma.

Painter unknown. National Treasure. Inscribed by Lánxī Dàolóng 蘭溪道隆 (1213–1278). Kamakura era, 1260s. Japanese hanging scroll, ink & colors on silk; H 108.2 cm x W 50.6 cm. Treasure of Kōgakuji (Kogakuji) Temple 向嶽寺 (Yamanashi Pref.) This is not the original painting, but rather a modern reproduction from this J-site

Closeup

RED-ROBED BODHIDHARMA (AT LEFT)

Says Yukio Lippit (Harvard University) in Awakenings: The Development of the Zen Figural Pantheon

The youngest son of King Xiangzhi, the faithful follower of Prajnatara's lineage. Seeing through the heretical views of the Six Sects in India He came to China and his teaching flowered into a beautiful five-petaled blossom, whose fragrance has now reached Japan. Auspicious signs are as endless as the Ganges. Shaolin Monastery -- the sprouting of the miraculous bud has not been hindered. Now it has rooted in the presence of a noble figure and is growing into an extraordinary flower. Respectfully inscribed for Layman Ronen by Lanqi Daolong, Abbot of Kenchoji. (Translation based upon Fontein and Hickman, Zen Painting and Calligraphy, p. 51, modified by the author.)

NOTE

Laymen Ronen. The inscription and painting appear to have been produced for the young Kamakura regent Hōjō Tokimune 北条 時宗 (1251-1284) sometime during the mid-to late 1260s, soon after Lánxī was reappointed abbot of Kenchōji (one ofKamakura's Great Five Zen Temples).

Episodes from Daruma's Life as Artistic Themes

Sekiri Daruma 隻履達磨

One Shoe Daruma

By Hakuin Ekaku 白隠慧鶴

(1685-1768). Ink on Paper

H 126.4 cm, W 56 cm

Eisei Bunko Foundation

Eka Danpi 慧可断臂. Literally "Eka cutting off his elbow." Such paintings derive from the Chinese legend of Huìkě 慧可 (Huike; Jp. = Eka), who becomes Daruma's successor and China's second Chan (Zen) patriarch. Eka is so eager to become Bodhidharma's student that he stands in the snow outside the cave (where Daruma is meditating) for one whole week and then cuts off his left arm and presents it to the master to demonstrate his resolve to undergo the hardships and rigors of Zen training. An early version of this legend appeared in the 8th-century Chinese text Denpō Hōki 傳法宝記・伝法宝記 (Chn. = Chuán fǎbǎojì, Chuanfabaoji).

Menpeki Daruma 面壁達磨. Literally "Wall-Gazing Daruma." Such paintings are based on the legend of Daruma meditating for nine years while facing a cave wall inside a cave near Shaolin Temple (China). This legend appeared by at least the mid-7th century in Chinese texts.

Royō Daruma 蘆葉達磨 or 芦葉達磨. Literally "Reed Daruma." This refers to a famous incident from his life, in which he crosses the Yangtze River on his way northward to modern-day Henan Province (China) while balanced on a tiny reed. Also sometimes translated at "Daruma on a Rush-Leaf" or "Daruma Crossing the Sea." However, the first textual reference to this river crossing [on a reed] dates from 1108 and the legend didn't become widespread until the 13th century.

Sekiri Daruma 隻履達磨. Literally "One Shoe Daruma." Such paintings feature Bodhidharma holding a single shoe and derive from the legend that Bodhidharma, after his death, came back to life and traveled home to India. On his return journey, a Chinese diplomat sees him walking barefoot and carrying one shoe in his hand. When the diplomat finally gets home, and tells this story, Bodhidharma's grave is opened and all that is found is one shoe. Paintings of this theme are the least common among the four, but Helmut Brinker has identified one dated to 1296 and inscribed by Nanpō Shōmyō 嘉禎元年 (1235-1309).

Eka Danpi 慧可断臂 (Lit. = Eka cutting off his elbow).

Hanging scroll, 1498. By Sesshū 雪舟 (1420-1506).

Sainenji Temple 斎年寺, Aichi Pref.

Photo from Kyoto National Museum

Sekiri Daruma 隻履達磨

Literally "One Shoe Daruma."

By Ejō Shinkai 慧定真戒 (1784-1853)

Photo this J-Site

NOTES ON EKA DANPI. The story of Eka cutting off his elbow comes in various versions. In the Annals of the Transmission of the Dharma Treasure (Chuán fǎbǎojì 傳法寶記; Jp. = Denpō Hōki 伝法宝記), an early 8th-century Chinese text attributed to Dharma-master Dù Fěi 杜朏 (Jp. = Tohi), we are told that Eka travels to Shaolin Temple 少林寺 (Jp. = Shōrinji ) in modern-day Henan Province (China) to ask Bodhidharma to teach him zazen 坐禅 (sitting meditation). But when he arrives, he finds Bodhidharma immersed in a meditation technique called "wall-gazing" 壁観 (Chn. = Bìguān, Jp. = Hekikan) or "wall facing" (Chn. = Miànbì, Jp. = Menpeki 面壁). Eka waits patiently in the snow for a long time (in some versions, for one week), until Bodhidharma informs him that Zen study requires discipline and hardship. Eka subsequently cuts off his arm and presents it to Bodhidharma as a sign of his sincerity and determination, as a sign of his willingness to undergo any sacrifice for the privilege of being Bodhidharma's pupil. Says JAANUS

This story is commonly interpreted as meaning one must be prepared to make sacrifices -- to go to any lengths to demonstrate a desire to learn and pass on wisdom -- for Zen cannot be transmitted to any dolt, but only to those few who are fit to trust. Indeed, the author of the Chuán Fǎbǎo Jì implies that the people who commissioned this work had taken a wrong direction in making the teachings available to greater and greater numbers. <see The Northern School and the Formation of Early Chan Buddhism

"I have no peace of mind. Might I ask you, Sir, to pacify my mind?"

"Bring out your mind here before me," replied Bodhidharma. "I shall pacify it."

"But it is impossible for me to bring out my mind," said the disciple.

"Then I have pacified your mind," said Bodhidharma.

Daruma Crossing the Yangtze River

This famous theme did not appear in texts involving Daruma until the 12th century.

Daruma crossing the Yangzi River

on a Reed (Royō Daruma 蘆葉磨)

Painter unknown. Japanese, Nanbokucho era (1336–1392), Hanging scroll, ink/colors/gold on silk.

H = 69.0 cm x 40.6 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Photo: Asianart

Daruma crossing the sea.

Tokai Daruma 渡海達磨, by Niiro Chūnosuke 新納忠之介 (1869-1954).

Wood. H = 110.6 cm (w/o base).

Photo courtesy

University Art Museum, Tokyo Nat'l University of Fine Arts & Music

Daruma crossing the

Yangtze River on a Reed.

Royō Daruma 蘆葉磨

By Shō-ami Katsuyoshi

正阿弥勝義 (1832-1908).

Photo courtesy

of this J-site.

WHAT DOES THE REED SYMBOLIZE? From a conventional viewpoint, it might symbolize the miraculous feat of crossing a mighty river while balanced on a tiny reed, or it might refer to "crossing to the other shore," or, as author John Stevens suggests, it could symbolize smooth sailing over the turbulent waters of samsara (cycle of suffering). But a growing number of art scholars think otherwise.Charles Lachman for instance, says the first textual reference to the river crossing [on a reed] dates from 1108, that the theme did not become widespread until the 13th century, and that the rushleaf [reed] motif should not be considered a biographical narrative, as heretofore believed. Scholar Bernard Fauresuggests a radically new interpretation. Since Daruma was, by the 16th century, considered a protector against smallpox and other epidemic diseases, Faure believes the reed was used by the Japanese to establish Daruma's credentials as an epidemic deity. Writes Faure: "Epidemic deities were related to water, and often came from the West, crossing large bodies of water. They were also expulsed on reed boats." <end quote>

Daruma, Epidemic Diseases, Smallpox, Owls, Dogs, & Toys

Special thanks to GABI GREVE

For obscure and complex reasons, images of Daruma (often accompanied by an owl, small puppy, and/or toy) became talismans against smallpox in Japan's Edo period (1615-1868). Such images were often red, for the smallpox deity (Hōsō Kami 疱瘡神) was said to like the color red, which symbolizes, among other things, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, and measles, as well as fertility, childbirth, and the caul (the embryonic membrane covering the head at birth). In those days, the common folk tried to please the smallpox deity with red images (Aka-e 赤絵, lit. "red prints;" also known as Hōsō-e 疱瘡絵, lit. "smallpox prints") in the hopes of averting illness or being granted a speedy recovery. Says Bernard Faure

Owl icons were used in the Edo era to ward off smallpox. Long life 壽 is written on owl's chest.

Photo GABI GREVE

Owl & Toy images were

used to ward off smallpox.

By Utagawa Kuniyoshi

歌川国芳 (1798-1861)

Photo Yamamoto Museum

Daruma, Dog, & Toy Drum. Red prints, like this, were used as talimans to protect kids against smallpox.

Photo J-source

Red print for girls

赤い羽子板 akai hago-ita.

Here Daruma is female.

By Utagawa Kuniyoshi ??

Photo GABI GREVE

Fan Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861). From series entitled Toys with Actor's Expressions (Sono omokage teasobi zukushi). Date 1842. A lion's mask, a Daruma doll, a female doll with bare shoulders, an owl, and a male doll playing with a piece of paper (fukigami). Date 1842. Photo Kuniyoshi Project.

Red-colored print with Daruma, owl, and toy drum. Used as taliman to

ward off smallpox.

Photo Prints of Japan

Closeup

of the Owl

Photo

Prints of Japan

KEYWORDS

Hōsō-e (Hoso-e) 疱瘡絵. Printed images (usually red in color) to protect children from smallpox (Hōsō 疱瘡). Also known as Aka-e 赤絵 (literally "red prints"), for the smallpox deity was said to like the color red. HŌSŌ 疱瘡 is the Japanese word for smallpox, while E 絵 is the Japanese term for painting, picture, or image. Hōsō Kami 疱瘡神 (or hōsōgami) is the Japanese god of smallpox, who first appears in the Nikon Shoki (日本書紀, approx. 720 AD). The disease, however, reached Japan much earlier, around the time of Buddhism's introduction (circa 550 AD). The disease was very dangerous. If the ill person's skin turned purple, it was considered serious. But if the skin turned red, it was believed the patient would recover.

Mimizuku みみずく (Owl), who is often shown together with Daruma in talismanic artwork aimed at warding off smallpox and illness in general.

Puppy Dog. A lucky charm, considered a symbol of good health in Japan. Usually made of papier-mache 張り子の犬.

RESOURCES ON THIS TOPIC

Eisai Co. Ltd. Online Museum.

Faure, Bernard. Scholar of Japanese religion, now at Columbia University. The Patriarch Who Came From the West. Daruma, Smallpox, and the Color Red.

Fujioka, Mariko 藤岡摩里子. Lost Owl and Laughing Daruma: Toys in Ukiyo-e Woodblock Prints in the Edo Period.

Greve, Gabi. Edo Toys and Talismans

Prints of Japan

Rotermund, Hartmut. Demonic Affliction or Contagious Disease? Changing Perceptions of Smallpox in the Late Edo Period.

Schumacher, Mark. Color Red in Japanese Mythology (this site). 2005.

Yamamoto Museum in Unzen City

Daramu's Evolution into a Phallic Talisman

Example of Daruma art lending itself to phallic symbolism (progression from left to right).

Daruma-ji Temple

少林山達磨寺 (Gunma)

Shinetsu 心越, founder of this temple, reportedly began a custom in the 17C of giving farmers pictures of Bodhidharma as a talisman to ward off evil.

Tokeiji Temple

東慶寺 (Kamakura)

By Hakuin Ekaku

白隠慧鶴 1685-1768.

See above link for inscription.

Tokeiji Temple

東慶寺 (Kamakura)

By Shaku Sōen

釈宗演 1860-1919.Menpeki (Wall Gazing) Daruma

from the rear.

Gabi Greve

Phallic Daruma

12 inches high.

Very special design.

As shown above, Daruma artwork lent itself easily to phallic symbolism without any need for folkloric references. Yet, there is little doubt that Daruma's metamorphosis into the male organ was pushed along by the widespread use in the late Edo era of the armless and legless Daruma tumbler doll talisman against smallpox. When knocked on its side, the doll pops back to the upright position and therefore symbolizes (1) a speedy recovery from illness, akin to "getting back on one's feet;" or (2) resilience, undaunted spirit, and determination. Such imagery can be easily employed to describe the down-up, soft-hard nature of the male sexual organ. With only a little imagination, one can easily understand why Daruma paintings and talismanic representations fell naturally under the same phallic sway. Says scholar Bernard Faure

Dated to 1926 (Aichi Prefecture). Photo: Ningyo-do Bunko 人魚洞文庫 Database (Osaka)

Daruma Tumbler Doll 達磨起上り、Wealth (Rice Bales) 貯金玉・俵・花巻人形、Cows 牛、Child 子供、Male Organs 陰茎

Daruma as a Woman

Pictorial example of Daruma (male) becoming Damura (female).

By Hakuin Ekaku

白隠慧鶴 (1685-1768). Inscription: Zen points directly to the human mind. See into your nature and become Buddha. Sumi on paper.

64.5 cm x 27.6 cm

Photo Israel Museum

By Yamaoka Tesshū 山岡 鉄舟 (1836-1888), the famous Meiji-era swordsman and calligrapher.

Photo:

Japanese Martial

Arts Society

Female Daruma, Fan Art 「女達磨」

Victoria & Albert Museum (UK)

ヴィクトリア&アルバート博物館蔵

by Utagawa Kunimaru 歌川 国丸 (1793 - 1829)

江戸 時代中期の浮世絵師

Photo this J-site.

In many ways, Daruma was the perfect candidate for female depictions and sexual symbolism.

The most obvious indicators are mentioned below <most come from Bernard Faure

In Tibet, China, and Japan, Daruma is said to be a manifestation of Avalokitêśvara (Jp. = Kannon), commonly known today as the Goddess of Mercy. Kannon was originally considered male in the Buddhist traditions of China and Japan, but starting around the 11th - 12th centuries, Kannon was commonly portrayed as female in China (less so in Japan). One of Kannon's female manifestations is Gyoran Kannon 魚籃観音 (lit. = Kannon with Fish Basket; Chn. = Yúlan Guānyīn), who in various old legends uses the bait of sexuality or promise of marriage to enlighten men. In the end, however, she remains a virgin. Her imagery as seductress was utilized as a didactic tool to help men overcome their sexual lust and break free of sexual desire.

Daruma's nine years of meditation facing a cave wall at Shaolin Temple in China is analogous to nine months within the womb.

Daruma's red robe, usually pulled over his head, symbolizes the placenta. Bernard Faure

The popular red-colored Daruma tumbler doll (which, when knocked on its side, pops back to the upright position) is akin to the penis (which falls and rises) and also to the resilience of the prostitute (who lies down and soon gets back up).

In Japan, the color red is not only the color of illness, but also the color of fertility and childbirth.

Daruma's role in protecting children against smallpox symbolizes rebirth and/or recovery)

Female Daruma 女達磨図 by Kitagawa Utamaru 喜多川 歌麿 (1753-1806)

Tochigi Kuranomachi Museum of Art 栃木蔵の街美術館. Photo this J-site

Daruma and Courtesans, Daruma and Prostitutes

Daruma Dressed as Harlot

Daruma Yūjo Isouzu 達磨遊女異装図

by Takeda Harunobu 竹田春信

(thrived mid Edo era).

Etsuko & Joe Price Collection.

Photo This J-Site.

Writes Daruma scholar H. Neill McFarland:

Keywords: Oiran 花魁 (courtesan), Yūjo (Yujo) 遊女 (harlot, prostitute), Geisha 芸者.

Daruma and Courtesan 「達磨と遊女図」

By Suzuki Harunobu 鈴木晴信 (1743 - 1807)

Says Daruma scholar H. Neill McFarland

Daruma and Courtesan 「達磨と遊女図」

by Katsukawa Shunkō 勝川春好 1743-1812

Daruma staring at a cave wall,

being tempted by a coutesan.

Photo This J-Site.

By Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 (1798-1861).

Date 1842. Artistic Performances of Daruma Monks (Tōsei Daruma no gei zukushi). Five variations of Daruma -- two squabbling women, one juggler, a male playing with a piece of paper (fukigami), and the actor Ichikawa Danjūrō VII as the aged Daruma, whose nose was so long that a thread, wound around his nose and one ear, would actually hold.

Photo: Kuniyoshi Project

By Kitagawa Utamaro 喜多川歌麿 1753-1806. A seller of fan-papers (jigami-uri 地紙売り) and two young beauties from an untitled series of eight prints published around 1797 by Tsuruya Kiemon 鶴屋喜右衛門. The idealised itinerant merchant has black fan-shaped lacquer boxes perched on his shoulder. In his hand he holds a fan with an image of Daruma eyeing the couple. Photo & text from Japanese Prints (London)

Daruma Watching the Action at Cherry Blossom Viewing and Sake Drinking Party 楼酒宴図

By Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-1889). Photo from Etsuko & Joe Price Collection

Daruma as a Woman

Pictorial example of Daruma becoming female in the popular river-crossing scene.

See Daruma Crossing the Yangtsu River for details on this well-known episode in Daruma's life, which did not appear in texts involving Daruma until the 12th century.

By Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831–1889). Royō 芦葉達磨. Daruma Crossing the

River on a Reed.

Photo from the

Muian Collection (J-Site)

By Katsushika Hokusai

葛飾北斎 (1760-1849).

Daruma Crossing the River on a Reed. Hanging scroll; ink

and color on paper.

H 104.2 cm x 43.2 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts Boston

By Suzuki Harunobu 鈴木晴信 (1743 - 1807).

Parody of Bodhidharma (Daruma)

Crossing the River on a Reed.

Woodblock print, ink and color on paper.

H 28.8 cm x W 21.6cm.

Museum of Fine Arts (Boston)

Daruma's Various Female Doll Forms

Onna Daruma 女達磨. Female Daruma.

Photo this J-Site.

Onna Daruma 女達磨. Female Daruma.

Photo this J-Site.

Anzan Daruma 安産ダルマ

Easy labor, safe delivery.

Photo this E-Site.

Mayu Daruma 繭達磨

Diety of Sericulture.

Photo this J-Site.

Ippitsu Daruma 一筆達磨

Daruma drawings created with a "single brush stroke" or quickly outlined in broad strokes.

Ensō (Enso) 円相

By modern artist Afaq Saleem

See below note about Ensō.

From poster advertising the March 2011 Daruma Fair at Jindaiji Temple

Photo: This J-site

By Soga Shōhaku 曾我蕭白 (1730-1781). Photo

Ensō (Enso) 円相. Ensō in Japanese means "circle." In Japan's Zen sects, the circle symbolizes enlightenment and perfection. It is a common motiff used by artists to express "unhindered movement" of brush and artistic spirit, and typically painted with a single stroke of the brush. For three Ippitsu Daruma drawings by Nantembō 南天棒 (1839-1925), see Bachmann-Eckenstein Exhibit 1991.

Daruma Dolls & Daruma Tumbler Dolls

Daruma dolls, still in their protective plastic wrapping

Sold at temple festivals and fairs, Daruma dolls are typically made of papier mache and depict Daruma in meditation. The doll comes in many sizes -- sometimes larger than a basketball. While most Daruma dolls are male, some Japanese localities have female dolls called Hime Daruma 姫達磨 or 媛達磨 (meaning "princess daruma") or Onna Daruma 女達磨 (meaning "female Daruma). In Kanazawa, for instance, Hime Daruma figurines are used as amulets for protecting babies <Frederic>, while nationwide, the parents of a baby girl generally purchase a Hime Daruma doll as a talisman to pray for their daughter's healthy growth <Greve>. Daruma dolls are also called "tumbler dolls" (okiagari koboshi 起き上がり小法師), for when knocked on their side, they pop back to the upright position. Such dolls are reportedly linked to a Japanese proverb associated with Daruma -- Nana Korobi Yaoki 七転び八起き(if you fall down seven times, get up eight). Its meaning? Resilience, undaunted spirit, and determination are the recipe of success. If at first you don't succeed, try try again. In another tradition involving Daruma, there is a Japanese saying "to have good luck" (Me ga deta 目が出た; lit. = eyes come out). According to Daruma afficiado Gabi Greve: "This means to have the higher number in a game of dice, and is itself a play on the word for 'congratulations' (ME-DE-TAI), so the eyes are important symbols of luck and winning. There are some Daruma figures, especially little talismans you can buy at temples or shrines, where the eyes pop out to invoke this saying."

Modern Woodblock by Artist David Bull

Paint in the left eye when you make your wish.

Paint in the right eye when your wish is granted.

Photo courtesy this J-site.

Daruma Kuyō 達磨供養

Daruma statues piled up before being

burned in a holy bonfire (usually

at year end). Photo this J-site.

Daruma Kuyō 達磨供養. See above caption.

Maebashi Hachimangū Shrine, 前橋八幡宮

Maebashi City 前橋初市まつり, Gunma Prefecture

Photo this J-Site.

Good Luck Daruma Dolls

Photo courtesy Gabi Greve

Daruma Kaigan / Kaigen 達磨開眼

Kaigan Shiki 開眼式, Eye-Painting Cermony

Daruma dolls are sold without the eyes painted in. At New Year time, before getting married, and at other important junctures in life, many Japanese individuals buy a Daruma doll, make a wish, paint in the left eye, then put the doll on their home altar or bookshelf. If, during the year, they are able to achieve their goal, they paint in the right eye while giving thanks. Many politicians, at the beginning of an election period, will buy a Daruma doll, paint in one eye, and then, if they win the election, paint in the other eye at a victory ceremony in front of their supporters. When your wish comes true, and the second eye is painted in, this issometimes called "both eyes pop open" (Me ga Deru 芽が出る or 目が出る or Me ga Deta 目が出た or Ryōme ga aku 両目が開く), a Japanese phrase meaning a winning roll of the dice (the eyes of the dice are called ME芽), a victory, a success, or the attainment of a goal or wish. At year end, it is customary for people to take their old Daruma dolls to a local temple, where they are burned in a big bonfire along with thousands of other Daruma talismans in a ceremony known as Daruma Kuyō 達磨供養. At such events, it is customary to purchase a new doll for the coming year and start the cycle once again.

According to Daruma scholar Kidō Chūtarō (Kido Chutaro) 木戸忠太郎, the selling of Daruma dolls with eyes began around 1764, a time when many children were afflicted with smallpox, which is especially dangerous for the eyes. A Daruma was then used at a talisman to protect from this eye affliction. Since a Daruma with no eyes painted has no special facial expression, the dealers soon sold Daruma dolls with no pupils painted and urged the customers to paint one pupil first and the second after they got better. This custom may have started around 1772. But with the vaccination against smallpox in the beginning of the Meiji period the use of eyeless Daruma as protector for the eyes also disappeared, or rather it changed to other departments of good luck in life.

The Daruma eye-painting custom is probably based on a much earlier Buddhist ritual called Kaigan Kuyō 開眼供養 (lit. eye-opening ceremony), in which a newly made Buddhist statue was consecrated by an officiating priest who would paint in the pupils of the statue's eyes, at which time (it is thought) the essence or soul of the deity would enter the statue. The first Kaigan Kuyō (eye-opening) ceremony in Japan occurred in 752 AD, when the officiating priest painted in the eyes of theGreat Buddha of Nara.

In modern times, there are numerous eye-painting ceremonies for Daruma dolls. Jindaiji Temple

The Daruma eye-painting custom, nonetheless, may have sprung from an entirely mundane source. Muses site contributor Gabi Greve (manager of the Daruma Museum Japan

Daruma Kuyō (Kuyo) 達磨供養

Daruma Memorial Service <below paragraph from Tokyo Metropolitan Government

Text & Photo Courtesy Japan Atlas: Traditional Crafts

Fuku Daruma 福達磨 (Lucky Daruma)

Says the official site of the Shōrinzan Daruma-ji Temple

Daruma Ichi 達磨市 (Daruma Fairs)

Daruma Fairs (selling thousands of Daruma dolls ranging in size from 6 cm. to 75 cm.) are held in many Japanese localities in modern times. Three Daruma Fairs are particularly popular and known as the Three Great Daruma Fairs of Japan (Nihon Sandai Daruma Ichi 日本三大だるま市と呼ばれている). They are held at:

Shōrinzan Daruma-ji Temple

Jindaiji Temple

Imaisan Myōhōji Temple

DARUMA'S OTHER ASSOCIATIONS

HORSES, MONKEYS, SHŌTOKU TAISHI, SERICULTURE

Topics Requiring Further Research

Monkey holding red Daruma doll.

Double Good Luck, Circa 1960.

Modern, courtesy eBay

Daruma's association with monkeys and horses is nebulous and convoluted. Let us begin with the monkey and horse motif. In Chinese and Japanese artwork, the monkey is often shown riding the horse. This symbolism stems from the 16th-century Chinese story Journey to the West, in which the Jade Emperor appoints the Monkey to the post of "Protector of Horses" to pacify the monkey's desire for power and recognition. The next link involvesPrince Shōtoku Taishi (574 - 622 AD), the first great patron of Buddhism in Japan, who according to legend was born in a stable -- the prince, by the way, is known by many names in Japan. Two of his names are Umayado 厩戸皇子 or Umayado no Ōji 厩戸皇子王子 (Prince of the Stable Door). When the prince was born, Bodhidharma (Daruma) supposedly manifested himself as a horse and neighed three times. <source Kidō Chūtarō, Ko Daruma Shū

The monkey and Daruma share other associations. Red-colored talismans depicting Daruma were used in the Edo period as talismans to ward off sickness and evil. Let us recall that the god of smallpox was said to like the color red, and red offerings were thus thought to pacify the deity. The monkey is also considered a talisman against sickness and evil, as well as the patron of fertility, safe childbirth, and harmonious marriage at some of Japan's 3,800 Hie Jinja shrines 日吉神社. These shrines are often dedicated to Sannō Gongen 山王権現 (lit. = mountain king avatar), the central deity of Japan's Tendai Shintō-Buddhist multiplex on Mt. Hiei (Shiga Prefecture, near Kyoto). The monkey is Sannō's Shintō messenger (tsukai 使い) and Buddhist avatar (gongen 権現). Even today, red-colored monkey charms are used in Japan to ward off demons, evil spirits, and sickness (see Migawari-zaru), and monkey statues are often decked in red clothing, the color meant to symbolize fertility and childbirth. The Japanese word for monkey (猿 saru) is a homonym for the Japanese word 去る, which means to "dispel, punch out, push away, beat away," and thus monkeys are thought to dispel evil spirits. Both the monkey and Daruma are associated with warding off illness, with fertility and childbirth, and with the color red.

The Edo-era distribution of red-colored Daruma prints (Aka-e 赤絵) to ward off smallpox involved both the monkey and the horse. Says Prints of Japan

Dated to 1912. Reportedly sold outside the gates of Asakusa Yukimonmae (Tokyo)

Daruma Tumbler Doll, Horse, Monkey, Quernstone, Pestle, Bells

達磨起上り、馬,、猿、臼と杵、鈴 (東京浅草雷門前にて売りしものなりと云ふ)

Photo: Ningyo-do Bunko 人魚洞文庫 Database (Osaka)

Prince Shōtoku Taishi, the Kataoka Beggar, and Daruma

Japan's medieval Tendai sect claims that Bodhidharma (after he died but then came back to life; see Sekiri Daruma above) did not return to India but journeyed onward to Japan, where he metPrince Shōtoku Taishi (574 - 622 AD), the first great patron of Buddhism in Japan. Says Bernard Faure

Says Gabi Greve

As mentioned earlier, Japanese legend says Prince Shōtoku Taishi was born in a horse stable, at which time Bodhidharma (Daruma) supposedly manifested himself as a horse and neighed three times. <source Kidō Chūtarō, Ko Daruma Shū

Sericulture & Silkworms

Keywords: silkworms, embryological, komori, incubation, reclusion, gestation (and its relation with an easy childbirth as well)

Says Bernard Faure

Says Gabi Greve:

Modern Mayu Daruma 繭達磨. Diety of Sericulture. Photo this J-Site.

Daruma features painted on cocoons.

Mayu Daruma 繭達磨

Photo this J-Site.

Silk thread in Japan called Daruma Ito,

or Silk Thread Daruma 達磨糸.

MUST READ, DARUMA'S EVOLUTION IN JAPAN

In his article The Patriarch Who Came From the West. Daruma, Smallpox and the Color Red, the Double Life of a Patriarch

How did the austere Chan patriarch ever become a tumbler doll? It is a complicated and obscure story. To understand it, we have to unravel many strands that were woven together into one figure. Daruma will thus appear to us successively as:

a malevolent spirit (goryō 御霊)

a crossroad deity (dōsojin 道祖神) associated with sexuality

a placenta god (ena kōjin 胎盤荒神)

"foreign" epidemic deity (god of Mt. Songshan 嵩山 and Shinra Myōjin 新羅明神)

a smallpox deity (hōsōgami or hōsōkami 疱瘡神); the Japanese god of smallpox,

a god of fortune (fukujin 福神)

Other elements contributed to his posthumous success. Let us mention for instance:

the symbolism of komori, incubation, reclusion, gestation, and its relation with easy childbirth on the one hand, and silkworms and sericulture on the other.

the color symbolism (red) and spatial (south): fire, exorcism, yang

the tumbling doll device (with its sexual connotations and its symbolism of rebirth or recovery)

This gradual entertwining of motifs was essentially realized during the medieval period.

READ THE FULL STORY HERE: The Patriarch Who Came From the West. Daruma, Smallpox and the Color Red, the Double Life of a Patriarch

A-to-Z Glossary of Daruma Forms in Japan

Adapted from Daruma Museum Japan

Great Teacher Bodhidharma Riding a Reed. Royō Daruma Daishi Nari

蘆葉達磨大師也 by Hakuin Ekaku

白隠慧鶴 (1685-1768). Hakuin was

one of Japan's most influential Zen

monks, teachers, and artists. He

turned seriously to painting and

calligraphy around the age of 60.

Photo from the Welfare Calendar

[Heart of Zen] 福祉カレンダー「禅の心], published annually by the Nyosui Association 如水会

Daruma with Protruding Eyes. Modern.

Me ga Deru Daruma めが出るダルマ

Photo this J-Site.

A-Un Daruma. Modern.

阿吽 だるま

Photo this J-site.

Matsukawa Daruma

Modern. This J-Site.

Daruma Whose Eyes Pop Out

Me Dashi Daruma or

Me ga Dete 目が出て

Modern. Photo this J-Site.

Kite. Modern. Blue-eyed Daruma.

Photo this J-Site

Kite. Modern. Blue-eyed Daruma.

Photo this J-Site.

Good-luck hand towel. Modern.

featuring Daruma and dice.

Photo this J-site

Snow Daruma (Yuki Daruma 雪達磨)

by Nantembō 南天棒 (1839-1925).

1921, Ink on Paper, 120 cm x 59 cm.

Photo: Bachmann-Eckenstein 1991

Daruma. Modern painting

by artist Afaq Saleem

Anzan Daruma 安産ダルマ. Easy labor, safe delivery. See this J-site.

Aoi Me no Daruma 青い目の達磨. Blue Eyed Daruma. Daruma is reportedly known as the "Blue-Eyed Barbarian" in some Chinese texts (although I have yet to find any reference). Nonetheless, in Japan, one can find blue-eyed Daruma dolls. See Kite images below.

A-Un Daruma 阿吽 だるま. The first and last sounds in the Japanese and Sanskrit syllabary; sometimes used to paint in Daruma's eyes. Details here.

Bikkuri Gyōten Daruma びっくり仰天 (Daruma looking at the sky; Bikkuri Gyōten is a Japanese expressive meaning sudden dismay, utter surprize, or stupefying).

Chinsō (or Chinzō) 頂相. Literally "head appearance." It refers to realistically painted or sculpted portraits of a Zen master's head.

Daruma no Me-ire 達磨の目入れ. Painting Eyes for Daruma. Also Me-ire no Daruma 目入れの達磨. Details here.

Daruma Sonsha 達磨尊者. Literally Lord Daruma, Honorable Damura, Venerable Daruma

Daruma-zō 達磨像. Generic term for Daruma statues or sculpture.

Daruma-zu 達磨図. Generic term for Daruma paintings and portraits.

Eka Danpi 慧可断臂. Paintings of Daruma's disciple Eka Danpi, who cuts off his arm as a sign of his serious desire to study meditation with Daruma.

Engi Daruma 縁起達磨 or Fuku Daruma 福達磨. Refers toLucky Daruma Dolls.

Enmusubi Daruma 縁結びだるま. Says Gabi Greve:

Fudō Daruma 不動ダルマ / 不動達磨 or Daruma Fudo 達磨不動. See Gabi Greve for details.

Fūfu Daruma 夫婦だるま (which can also be read Me-oto Daruma). Mr. And Mrs. Daruma, or Loving Couples. Artwork of the pair is sometimes combined with the famous Takasago Legend 高砂伝説 of a happily married couple. Says Gabi: "A memorial day for happy couples is the second day of the second month (Feb. 2), since FU means TWO. Some hotels and restaurants also give special reductions for couples on the 22nd of any month........You buy them as a pair and keep them to remind you of the endurance and perseverance it takes to make a marriage sucessfull. They are sold at special temples and shrines dedicated to finding and keeping a partner for life." See Gabi Greve for details.

Fuku Daruma 福達磨 or Engi Daruma 縁起達磨. Refers toLucky Daruma Dolls.

Gankake Daruma 願掛け達磨. Daruma to Make a Wish. Also called Menashi (Me-nashi) Daruma 目無し達磨 (Daruma Without Eyes). Details here.

Hanshinzō 半身像. Bust portraits.

Hisshō Daruma 必勝だるま. Victory Daruma, used by politicians who win elections. Also known as Senkyo Daruma 選挙だるま (Election Daruma). See Gabi Greve for details.

Inka 印可. A portrait given by a master to a student as a certificate of the student's attainment of spiritual awareness and as a symbol of the clear and unbroken lineage of a sect. These portraits often include hōgo 法語, or words of religious enlightenment, inscribed by the priest depicted. A portrait done in a realistic and detailed style, together with an inscription, provided the disciple with both the tangible presence and the inspiration of the teaching of his master long after personal relations were severed through parting or death. <source JAANUS

Ippitsu Daruma 一筆達磨. Portraits created with a "single stroke of ink or brush," yielding pictures that are sometimes barely recognizable.

Keshin 掛真. Portraits hung or placed together with imaginary portraits of Zen patriarchs (zenshū soshizō 禅宗祖師像) in the dharma hall (hattō 法堂) or the main gate (sanmon 三門) of Zen temples for use in conjunction with memorial services. Chinsō sculpture belongs entirely to the keshin category. Keshin portraits were made after the master's death; inscriptions were usually added by close contemporaries. The goal was to symbolize the personal relationship between master and disciple, and artists were encouraged to go beyond the mere physical likeness of the master to capture something of his inner spirit. <sourceJAANUS

Komochi Daruma 子持ダルマ. Fecundity Daruma, to ensure fertility and safe gestation.

Kotobuki Daruma 寿だるま. Long Life Daruma. Special talismans (dolls) are sold to ensure a long and productive lifespan.

Matsukawa Daruma 松川達磨. This particular Daruma doll is decorated with numerous symbols of fortune, including a treasure ship, pine/bamboo/plum trees, a carp swimming up a waterfall, the god of luck Ebisu, and the auspicious motif known as "ichi-fuji, ni-taka, san-nasubi" (Mt. Fuji first, hawk second, eggplant third)." According to one widely accepted opinion, this doll is named after Matsukawa Toyonoshin 松川豊之進, a retainer of the Date clan about 170 years ago and the creator of this doll style. Details here.

Mayu Daruma 繭達磨 or 百達磨 (lit. Cocoon Daruma, One-Hundred Daruma). The embryological symbolism that associates Daruma with silkworms. In this connection, one can purchase silk thread in Japan called Daruma Ito, or Silk Thread Daruma 達磨糸.